There’s just a handful of countries where the word sanctions has a personal meaning to everyone. These are countries like Iran, Cuba, and Syria. The rest of us see sanctions as something abstract: like one country punishing another for bad behavior. Usually, a democracy punishing a non-democracy. It must be a good thing, right?

But in a conflict between two states, it is always ordinary people who are caught between two fires. With international sanctions, they deal with double pressure: of their own government and of other countries, which in many ways is not less significant.

I visited Iran four times to learn about Persian design, meet entrepreneurs, architects, artists, and learn how they live. I saw how international policies on Iran, the same policies democratic governments issue over human rights violations or alleged hostility, end up harming ordinary people in brutal, unexpected ways. Like the import ban that has left Iran with one of the oldest air fleets and one of the highest airplane crash rates in the world. Other restrictions make it hard for people to work, travel, study, use digital services, and build relationships with the world.

There’s little empathy for people in isolated states because the world knows little about them. But looking into what international sanctions mean to ordinary people is a crucial part of the conversation on discrimination and privilege.

Here’s the complete guide on the US, EU, UN sanctions on Iran from the perspective of an ordinary person.

What are these sanctions in the first place?

The sanctions imposed over Iran are among the world’s strictest, influencing almost all industries from international trade, energy, shipping, to banking, healthcare, and travel.

It all started in 1979 with the the Iran hostage crisis, but the sanctions were expanded multiple times since then. Latest sanctions were added by the US and the EU in response to Iran’s uranium enrichment program and human rights violations.

One would expect sanctions to target the government officials, with an aim to influence their policies. In reality, economic sanctions on Iran put maximum pressure on the population. They have had a devastating effect on the Iranian economy and continue playing a defining role in the people’s lives.

In 2021, the official inflation rate in Iran was around 45 percent, with at least half of the population struggling below the poverty level. Inflation is impossible to attribute solely to international policies, but they clearly correlate.

💸 Banking: bye-bye to Visa, Mastercard, and cross-border payments

Iran is disconnected from SWIFT

Essentially, cross-border payments are banned by the sanctions. People who work or study abroad have no legal means to send money to families back in Iran.

I bought a 🖼 painting from a street painter in Tehran two years ago. As there was no way to pay him directly, we asked local galleries for help. The bank transfer had to go to London and then to Dubai, from where somebody delivered the money to Iran in person.

Visa, Mastercard (and other providers) are banned from operating in Iran

The US bans these companies from operating in Iran. International debit or credit cards don’t work in Iran, and it’s not even possible to withdraw money from them. Even tourists have to bring money in cash.

Even outside of Iran, bank accounts are being shut down

The only way for an Iranian to access international payment methods is to open a bank account abroad. Many go to nearby Georgia or Armenia for that. In recent years, many of these accounts are getting closed. This is due to the agreements of these countries with the US to limit access to international banking for Iranian citizens.

Going abroad is a nightmare

Paying for accommodation on Booking.com or Airbnb or using services like Skyscanner to purchase flights isn’t possible as international payments methods are not available to Iranians.

A couple of years back, I had architect friends from Iran visiting me in Europe. They couldn’t pay for anything from Iran, and I had to book hotels, flights, and even buy bus tickets for them to be able to travel.

No legal way to get paid from abroad

It creates a curious situation where most teachers and translators of the Persian language on websites like Upwork, Fiverr, or Italki do not live in the country of its origin.

🛠 Infrastructure: how flying in Iran became unsafe

Years of sanctions have left passengers with one of the oldest air fleets in the world. The average age of a passenger airplane is more than 25 years. Sanctions prevent importing airplane parts and inviting international crew for airplane maintenance.

When the US sanctions were about to be lifted by the Obama administration in 2016, Iran announced their intent to order 100 Boeing airplanes, a deal worth billions that would be one of the largest orders for Boeing. The Trump administration reversed the agreements.

The ban on importing airplane parts produced in the US has left Iran with no choice to modernize its fleet. In 2017 Iran tried to purchase Sukhoi airplanes from Russia, but the US blocked the deal last-minute due to some airplane parts being manufactured in the US.

In 2019, a technical error forced a Norwegian Air jet to land at Shiraz Airport in Iran. It needed technical assistance. Neither experts nor parts could be imported to Iran. It spent nine weeks grounded in Shiraz before it managed to return back to Norway.

🌎 Software privilege: Slack, Coursera and others ban users with ties to Iran even if they have left the country

Many apps and services we use every day are owned by companies based in the US. Most of these companies are banned by the US government to provide services to Iranians.

On many websites out there, Iran is just missing from the list of available countries.

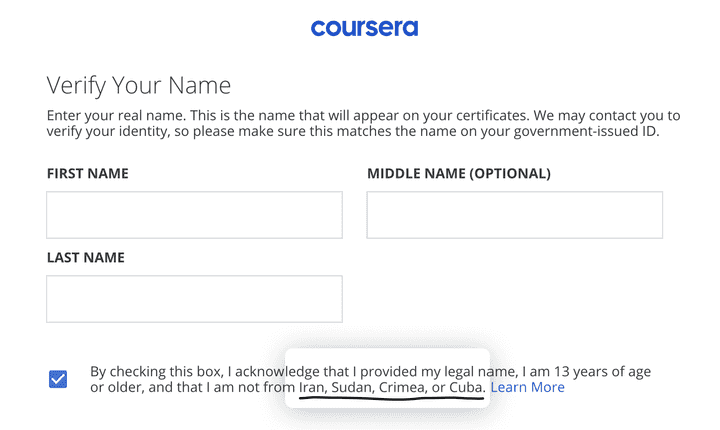

Even Coursera, a company pioneering accessible education, explicitly bans Iranian users from the website.

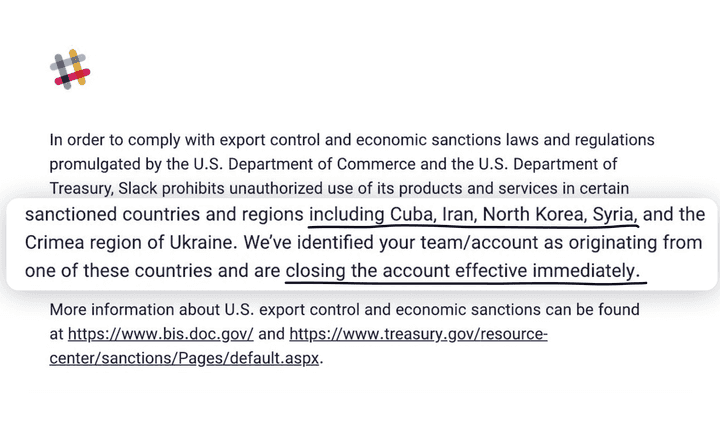

With Iranian users being a small fraction of the user base of those services, most of them don’t bother checking if the accounts blocked are actually based in Iran. Slack goes as far as to block and remove accounts of users who have visited Iran, even if they are have long left the country.

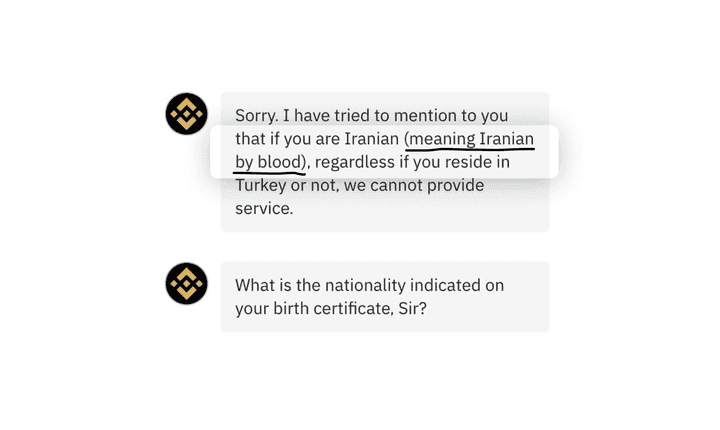

Binance, in response to one of the users, says that “service won’t be provided to Iranians by blood” (which is illegal no matter how you look at it).

Cloud services like Google Cloud or Amazon Web Services are also unavailable to Iranian developers, although it’s not required by the sanctions.

💙 Health: limited access to drugs and medical equipment

Sanctions, despite the humanitarian exemptions, limit hospitals from purchasing essential medicines and medical equipment for critical medical care. It also has affected the coronavirus situation in Iran.

Human rights watch reports that the worst-affected are Iranians with rare diseases and conditions that require specialized treatment. They are unable to acquire previously available medicines or supplies.

🚌 Travel: US student ban and highest visa refusal rate in the world

In 2019, the US banned Iranian engineering and science students from studying in the country. Hundreds have faced deportation and visa refusals.

The refusal rate for Iranians applying for visas to the United States was about 89% in 2020. Only one out of ten applicants gets their visa approved, and the application fees are not returned to the rest.

📦 Secondary sanctions: a whole new mess

All of the above are sanctions imposed directly on Iran. The concept of secondary sanctions employed by the US makes everything more complicated.

Essentially, the US reserves the right to put penalties on any country or company that doesn’t follow the same sanctions as imposed by the US.

Here’s an example: a friend of mine is an Iranian teacher in Vietnam 🙋. She went to the post office to ship a 📦 parcel to her family in Iran. She couldn’t do it, even though Vietnam has no sanctions on Iran. The shipping company was forced to refuse service to her to avoid secondary sanctions. Yes, it’s that crazy.

Born in the wrong place?

Can access to goods and services be denied based on place of birth? It feels absurd to say how access to Slack and daily banking are fundamental human rights — until you see how millions are denied access to them. It’s not about apps and banks though, and for some goods in question, sanctions leave people with no real alternative — as with airplane parts, placing Iran’s air travel among the most dangerous in the world.

The situation where the passport you’re born with defines your access to goods creates inequality that’s impossible to bridge. Like with discrimination by skin color or gender, it is a mark one carries their whole life. But it’s often not seen as such. When two countries are involved, it’s not called discrimination anymore; It’s international relations.

This article is being updated all the time. I thank Sina Fakour and Armita Nemati for their contributions. Feel free to reach out at roman@musatkin.com with comments and suggestions.